The album begins with 11 minutes of dramatic synths and guitar riffs in “Funeral For a Friend / Love Lies Bleeding,” an admittedly odd start for what is yet to come. Though, what it does have in common with the next 16 tracks is how experimental it is. The ‘70s were definitely a time for exploring sound, and Elton John decided to do that in one project. There was much room to work with considering it’s a double album, allowing for songwriter Bernie Taupin to broaden his horizons to topics ranging from the death of Marilyn Monroe to the fantasies of rock and roll.

The next track, “Candle in the Wind,” is a touching tribute to the exploited actress. John is able to show a different side of Monroe that her legacy did not show. “And even when you died / Oh, the press still hounded you / All the papers had to say / Was that Marilyn was found in the nude.” The song became an instant classic. Those who had lost a loved one felt a great connection to the track, and when John changed the lyrics for Princess Diana’s funeral in ‘97, all of England adored the revision, turning this version into the number one chart hit of all time. This ballad introduces an intimate environment, interrupting the whimsical tone being set by the story so far. This break in the fast pace album repeats throughout, switching from upbeat rock & roll tracks to slower songs that gently wring out a narrative rather than yell it at the audience (e.g. “Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting)” to “Roy Rogers”).

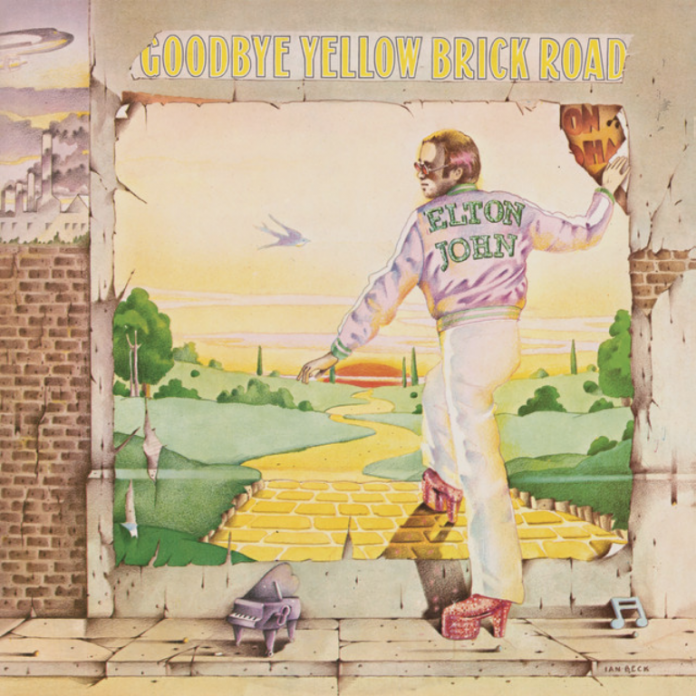

Just like “Candle in the Wind” tells the story of a star pushed to her limit, “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” presents an artist that seeks his old life. The title track dives deeper into the The Wizard of Oz allegory, as John compares the life of an artist who has lost himself to Dorthy being lost in the land of Oz. Not many artists admit to missing their life before fame, but John elaborates on the false narratives that the music industry produces in order to keep their artists. “Maybe you’ll get a replacement / There’s plenty like me to be found.” The music matches the mystical world that John is alluding to. The background vocals swell as John sings about his fleeting youth and having to experience the blues before he’s even old enough to fully grasp the realities of stardom. As the chorus progresses, the piano keeps a steady pace with the guitar as John pleads for his life beyond the shiny road to success.

Not only do John and Taupin explore the changes that the industry has on them and their lives, but they also build a bridge between the rhythm and blues they were raised with and the rock and roll scene of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Within the carnival-sounding chaos of “Your Sister Can’t Twist (But She Can Rock ‘n’ Roll)” is the story of a young girl helping the boys get with the times. “Throw away the records ‘cause the blues is dead / Let me take you, honey, where the scene’s on fire.” This new sound of the ‘70s caused much tension between the kids of the time and the adults of the previous generation. Rock and roll was loud and obnoxious to the older generation, but kept the same message of struggle that rhythm and blues exhibited. “Bennie and the Jets” is a play on the worship of bands at the time, where Taupin decided to create a fictional band similar to what The Beatles did with Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band; the applause at the beginning and end of the track is also a clever call back to Sgt Pepper’s.

“Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting)” was an interesting choice for the leading single. A satirical take on bar fights and masculinity made its way to the radio stations and became an immediate hit, getting people excited for the album—maybe a little too excited. Though it’s a fantastic song, it set an aggressive precedent for the project that the tracklist was not able to hit. Intelligently, it was followed up by the title track as the next single, preparing listeners for ballads as well. The electric, fast-paced, anger-filled track is just so much fun. It’s the type of music the 16-year-old girl was raving about in “Your Sister Can’t Twist (But She Can Rock and Roll).” In contrast to “Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting),” Taupin writes a sapphic tragedy.

“All the Girls Love Alice” is an underrated track on the album. Once again, we have a 16-year-old girl at the center of the song; this time she’s experiencing the discovery of sexuality while trying to keep her high-profile status. John sings, “Poor little darling with a chip out of her heart / It’s like acting in a movie when you got the wrong part.” We find out that the young girl has died in the subway with no indication of how. A bluesy, fast-paced tempo keeps the verses going until the music pauses during the chorus. This was the first queer storyline that John & Taupin had written, and it was released three years before he came out as bisexual in Rolling Stone’s 1976 cover story. “All the Girls Love Alice” paved the way for John to become an icon in the LGBTQ+ community.

Taupin really enjoys telling stories of people who have just let themselves go on this album. It seems like the subjects of “Dirty Little Girl” and “Social Disease” would be a perfect match: two people who smell so badly. I like to think the woman in “Dirty Little Girl” is also one of the ladies “falling apart at the seams” in “Social Disease.” Now, this is a simplified conclusion of two humorous songs that mean much more than what is presented at the surface. The characters of these two songs directly contrast those that have achieved fame. At first, “Dirty Little Girl” seems like it would be about a promiscuous woman, but it turns out that she is literally dirty. She, in turn, has become a social disease. The man is a drunk, the woman needs a bath, but this doesn’t make them any more depressed than the stars that Taupin has written about in the previous songs. There have been times in John and Taupin’s partnership when they create tracks for the fun of it, and these two songs are a perfect example.

Goodbye Yellow Brick Road is an album that dissects the different characters of life in the ‘70s. The young trendsetters, rock and roll fanatics, those still stuck in the ‘50s, and the burnt out artist. In the end, John feels more connected to his life before fame than the rockstar life he and Taupin created. Ironically, this project made the pair more famous than ever; but after decades of touring, there is no other album that better reveals why they feel the need to stop now and veer away from the yellow brick road.