Well, you heard about the time/But not all of it is true

And you’ve read the magazines/I’ve been wounded by folklore.

– “A Lonely Song”, Daniel Johnston (1990)

If you have ever met a shaggy-hair-music-Bro you probably know who Daniel Johnston is. Something about Johnston’s cult-status between fame and obscurity says, “I’m fun to talk about at parties”. They, the Bros, find you wherever they can. Sometimes it’s during a lull in a conversation, but usually when you clearly want to be alone. The Bro uses terms like “outsider” and “visionary” and whatever other Pitchfork-lingo they can muster. Their praise reads more like verbal white-out on Johnston’s name, over which they sketch in their own. Maybe it’s enough to secure a date, maybe you’ll think they are that much cooler, either way Johnston’s artistry factors little into their orchestrated meet cute. Fortunately for us, Ro2 Art takes a definitive step away from the Bro-mentality with their retrospective, “Daniel Johnston: Story of an Artist & Songs of Pain”.

By the time I arrive at the gallery, a group of visitors has already got their fill. These are the die-hard Johnston fans. A noon opening is child’s play compared to the hours spent waiting in line at any number of concerts in the Texas summer heat. Some of them fit the Bro description, but most are just early-bird devotees. A slightly nervous, mostly excited greeting from Jordan Roth, Ro2 Art co-owner (and my boss), says, “We’ve got a long day ahead of us”. Yes, I have worked at Ro2 Art for about six months. If an unpaid internship constitutes an insurmountable conflict-of-interest for you: close this tab, power off your device and go see the exhibition for yourself.

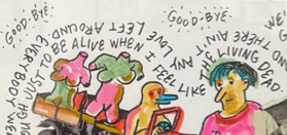

I’m introduced to Marjory Johnston, the artist’s sister, and her partner Terry Talley. Terry mans the merch stand, while Marjory gives me a tour of the back gallery. Pieces in the back date from the latter-decade of Johnston’s life up until June 2018, just a year before his passing. I can’t help but think of an elderly Johnston, lifting a wrinkled hand to his sketchbook and painting cute ducks as stand-ins for an eulogy. There’s nothing especially unique about this piece at first glance. Recurring characters like prismatic cartoon ducks and disembodied torsos form a less-than-holy conversation. It seems oxymoronic to say, given his insistently variable style, but it was textbook Johnston. Marge tells me he was only fifty-nine when he suffered a fatal heart attack. Too young for “elderly”, too young for “eulogy”.

When I take a second look, a pair of starburst “Good-byes” speak prophetic volumes, something like: “I knew it, but I wish I didn’t”.

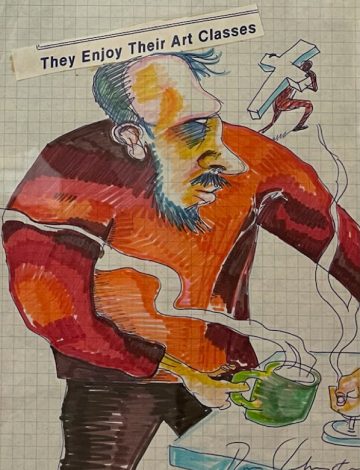

Solomon Kane, Johnston’s caretaker late in life, tells me about how Johnston developed schizophrenia a couple of years into his education at Kent State University at East Liverpool. The more I learn about Johnston, the more convoluted his aphorisms seem. What did he mean when he pasted a paper clipping that says, “They enjoy their art classes”? Maybe it’s tinged with disgust towards academic standards, maybe some kind of retroactive jealousy. Maybe I’m just imagining treasure where there is no chest.

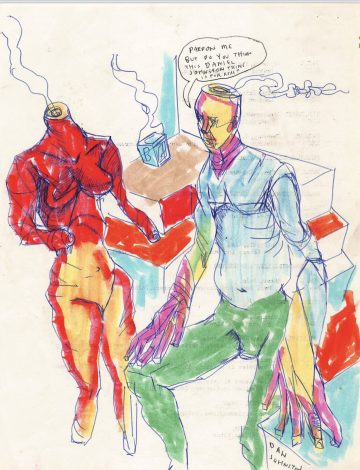

Johnston maintains a Hitchcock-level mystery within his pieces. Any and all nuance seems incidental, happenchance and pure. He seems to have known we can’t help but dissect art for its stylistic systems and narrative complexity. Even contrarians offer their compulsory “it is what it is” analysis, which is equally unsatisfying. One piece asks, “Pardon me/But do you think this Daniel Johnston thing is for real?”. If Johnston is asking, who the hell are we to guess?

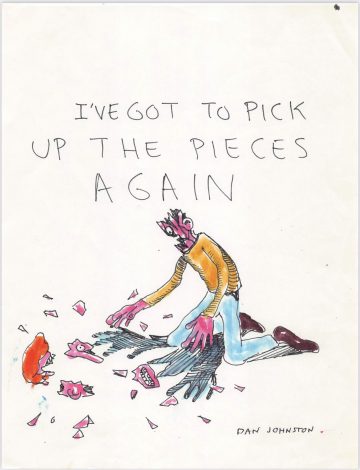

Pieces spanning almost four decades fill the front gallery walls. I was gone for install, so the exact order of the pieces is lost on me. I’m told the difference in frames separates Johnston’s work based on time-period. Strict rows continue chronologically in a clockwise pattern, the resulting centripetal effect stirs the viewer into an experiential cocktail. Like any strong cocktail, it gives you the spins until you step back and admire the grander whole among the parts.

Whether Johnston writes through a third-person narrator, Captain-America knockoff, or towards a nondescript audience, his pieces from the 70s block-off a noticeable distance from the viewer. A notable piece features a lobotomized figure speaking to a decapitated torso (a typical scene for Johnston). Jagged, yet by all accounts intentional, marks suggest more than delineate. Johnston’s pieces form mischievous compositions, boldly refusing to color inside the lines. It’s something you would expect from a figural-Cy-Twombly, or maybe a Dali-Comic-book. Entrancingly capricious.

The crowds hold strong throughout the day. A few Bros come in, but mostly middle-aged fans who grew up listening to Johnston. A deep nostalgia lingers throughout. Everyone brings their own folklore, their own stories. I’m sure, over the course of my writing, I have let on to my own.

I suggest, aside from my “conflict-of-interest”, you see the exhibition for yourself. If not for the pieces, then to discover your own myth. I even attempted to omit much of Johnston’s biography as:

-

- I really don’t think it is necessary

- The pieces speak better for themselves

Ultimately, Johnston’s work holds an oddly transformative power, turning strangers into distant (or even close) relatives. At Ro2 Art, all that is great about Johnston, the substance of the man and myth, is upfront and refreshingly salient. A posthumous spotlight shines on Johnston, trimming back years of obscurant lore. What remains is something off-kilter and roughly polished: a twilight-zone-sketchbook with songs of pain and pleasure.

“Daniel Johnston: Story of an Artist & Songs of Pain” is currently on view at Ro2 Art in the Cedars (1501 S. Ervay St. Dallas TX, 75226), through July 31st.