When I was around 10 years old, I fetishized the entrepreneurial works of Walt Disney. With help from my family’s many trips to Orlando and Anaheim, I viewed the early years of the animation auteur’s career as an untouchable relic of American popular culture, albeit subconsciously, through purchases of DVDs, shirts, stuffed animals, and resort vacations. I still hold a special place in my heart for Mickey Mouse, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, and the iconic art style they existed within (see also: my recent obsession with Cuphead). Though in my early adulthood, I’ve taken into account the company’s many faults: blatantly offensive stereotypes in the early cartoons, Walt’s alleged anti-semitism, and of course the enterprise’s frightening monopoly on the entirety of media as we know it (Marvel, LucasArts, etc). I may look back at those years and wince, but I think I can effectively incorporate that old interest into my own identity while acknowledging its conflicts with my political alliances, as well as recognizing that I’m not directly responsible for the societal harm the corporation may subtly contribute to by watching the Lion King reboot.

Elizabeth Woolridge Grant knows this feeling of reconciliation. To put it bluntly, her career trajectory as Lana Del Rey has been an eyesore up until recently. She felt like an industry plant from the beginning, landing talk show appearances out of thin air, boasting a deal with Polydor and Interscope right out of the gate, and dangling a laughably shallow baby-mobile of 50s and 60s Americana imagery over her music, videos, and press photos. Across her first several albums, she told the same story every time in the same dejected croon: innocent cigarette-cradling damsel falls for gritty, tattooed, leather-donning bad boy. Tied together with a baroque-meets-hip-hop instrumental ribbon, it made for the perfect stocking stuffer for any Urban Outfitters disciple.

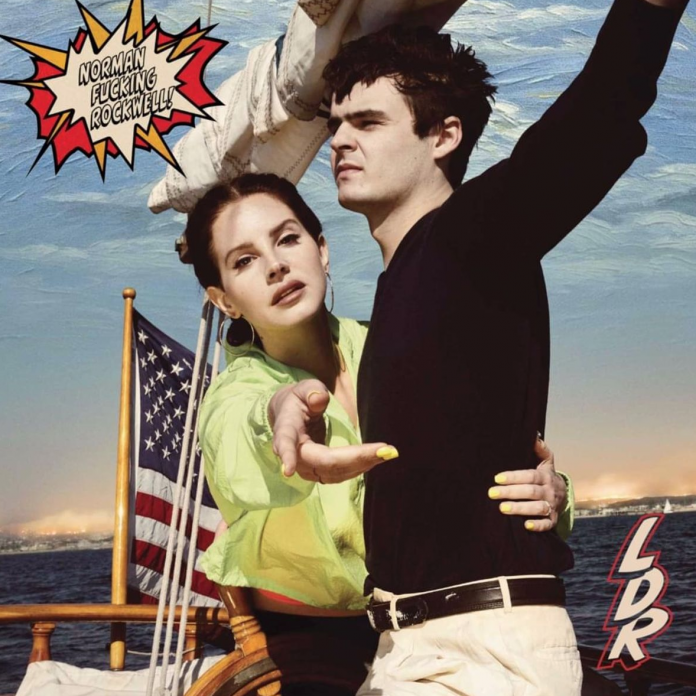

On Norman Fucking Rockwell!, Lana dismantles that poor façade with the first lyric: “Goddamn, man-child.” It becomes pretty clear pretty quickly that her real self has been hiding behind the weak iconography with something genuine to say this whole time. Nearly every track on this 70-minute record completely flips the script and shatters every previous narrative as if Born To Die, Ultraviolence, and Honeymoon never happened. The abhorrent male gaze that informed her previous songs has been ripped to shreds, and in its place a bold statue of liberty and liberation has been erected. Lana is openly conflicted, pissed off, and fed up with the America she once idolized so dearly, and the result is a true first for her: a bright, sharp, uncompromising pop album.

On Born To Die and Ultraviolence, Lana Del Rey wore the American flag like a Joy Division t-shirt. The allusions to tattoos, alcohol, cigarettes, Lolita, Nancy Sinatra, fast cars, and kissing in the rain all posed together as a substanceless collage of nostalgia for nostalgia’s sake. For cryin’ out loud, her very stage name is partially a reference to an actress “frequently cited as a popular culture icon of Hollywood glamour.” However, in the wake of her country’s corporate nightmares lighting up the global stage via the worst presidency in modern history (etc, etc, etc), Lana’s pet obsession with the 50s and 60s has undergone a radical metamorphosis. Norman Fucking Rockwell! (note the wholly unsubtle wedging of FUCKING into the name of a quintessental proprietor of the “American Dream”) is a more complex synthesis of American cultural references and iconography, and Lana uses this imagery to channel her tangled feelings on the nation and her relationship with it. Her love and hatred for the USA come through on the track “The greatest,” which basically eulogizes the world as we know it. And while I could do without “The culture is lit / and I had a ball,” her tender lyrical farewell is a cutting bulls-eye: “Kanye West is blond and gone / ‘Life on Mars?’ ain’t just a song / I hope the livestream’s almost on.” She acknowledges our endlessly flawed existence, and invites us to join hands as the Earth catches fire.

Listen to the album here!

Lana could always write a song, of course. I still get “Video Games” stuck in my head from time to time. But across each record, it’s been very unclear what style felt right for her songwriting. On Born To Die we heard an intriguing revision of 60s baroque pop; on Ultraviolence a malaise-glazed take on desert rock, and on Honeymoon and Lust for Life? Your guess is as good as mine. But here, she’s finally found her most advantageous aural palette: the piano ballad. Norman Fucking Rockwell! is full of them. From the show-stopping title track to the uplifting “Mariners Apartment Complex” to the positively tragic “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have – but i have it,” Lana’s two-armed embrace of classic rock and AOR finally makes sense, with her sensual contralto vocal (which has improved monumentally over the past eight years) tumbling gently over lilting keyboards with an elegant poise.

What also makes Lana Del Rey’s fifth album monumental is stylistic cohesion and consistency, which is (reluctantly) thanks to none other than Jack Antonoff. Lana’s worst records suffered mostly at the hand of the overload of several different producers and features from different walks of life who throw the songs in too many conflicting directions (take Lust for Life, which features both Stevie Nicks and A$AP Rocky). In contrast, Jack Antonoff’s autonomous production work makes every song on this album feel at home with one another. Norman Fucking Rockwell! boasts a refreshing composite of Lana’s favorite elements of psych and classic rock, with nods to the best sounds that popped up on her previous albums. While much of the record goes more in the clean, upfront organic rock direction–with Lana’s voice FINALLY brought to center stage with little digital alteration–she hasn’t lost touch with some of the orchestral dream pop that she made her name with, especially with the song “Cinnamon girl” and the excellent “The Next Best American Record.” Not to mention the monolithic psych-jam outlier “Venice Bitch”–probably my favorite Lana Del Rey song ever–full of swirling guitar and analog synth solos and kaleidoscopic vocal refrains, really setting her apart from her top 40 pop contemporaries. After so many lackluster tracklists, this album finally feels like a satisfying and cogent collection from nearly front to back.

I’m just as surprised as you are. It really feels like this has been too many years in the making; in 2011, the blogosphere was so ready to crown Lana Del Rey queen of refreshing, emotional indie pop, only to be let down with the horrid clichés and hollow indulgences that flooded her early discography. But after hearing the mature, emotionally perceptive writing and exhilarating sounds of this inaugural and astonishing success, I think this is the Lana Del Rey we were meant to hear all along.